Our voice from the field in this issue of AI Practitioner is Nelly Nduta Ndirangu from Nairobi, Kenya. Nelly’s compelling and unwavering commitment to bringing communities together and, through their differences helping to create common ground, is a true symbol of appreciative practice in the world. Her understanding and creative use of Appreciative Inquiry (AI) is a heartening example of its universal appeal and value which, for the communities Nelly continues to work with, has reassured and consequently reinforced their sense of identity and shared meaning. – Keith Storace

Cultivating Appreciative Communities

As well as presenting this work at the World Appreciative Inquiry Conference (WAIC) 2015 (1), my involvement in the co-authorship of Tukae Tusemesane – Let’s Sit Down and Reason Together: Enlivening Strengths and Community (2), has greatly motivated me to apply appreciative actions in my own community.

In my capacity as a counselling psychologist, along with other psychologists, I helped lead the development of evidence-based programs that supported victims of post-election violence in Kenya; peace-building initiatives; and resettlement programs for internally displaced families in 2007/2008. This year, the Taos Institute has funded a similar peace-building program through the Kimo Wellness Foundation (3) of which James Karanja, also a Taos Associate member, and myself are the lead team. I enjoy using appreciative skills with my clients, trusting that the appreciative approach helps them to deal with unpleasant case scenarios in their lives. Together with the Kimo team of counsellors, we have tailor-made a comprehensive AI trauma-based healing program to reach out to

affected communities that occasionally suffer from common traumatising experiences, such as being the victims of terrorism, landslides, massive road accidents and incidental fires in schools, among others.

Also along the lines of a strengths-based approach, I have been involved as the in-country project coordinator in Kenya, collaborating with William James College (Massachusetts, USA) and the Kimo Wellness Foundation in the

development and implementation of a strengths-based curriculum for students and pupils. Together with a team of professionals, we have borrowed extensively from the AI model to add value to the kind of education being delivered to children in Kenya. The approach has brought together parents, community and teachers to experience learning that is later cascaded to their children in the school setting. The role of each group is identified and appreciated for the wellbeing of this young generation of learners. This has popularised my work in schools within Kiambu and Muranga counties.

Realising common goals, appreciating differences

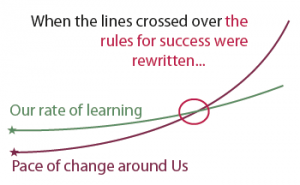

The climax of this work occurred during the month of February 2017, when I was invited to train 525 students from twenty-three different schools in the Mount Kenya region, at Our Lady of Consolata Mugoiri Girls’ High School, during the school’s second annual peer-counselling day. The theme this year was ‘Overcoming Youth Challenges in the 21st Century’. This led to another training opportunity, scheduled for July 2017, at the Njiiris High School, one of the national schools in Muranga county.

Given my level of responsibility as the person in charge of the Kimo team, I worked hand-in-hand with Claire Fialkov and David Haddad, both professors from William James College in Newton, Massachusetts, USA, and James Kamau, counsellor and teacher in Muranga county, in connection with their respective research focus, including ‘Research as Future-Forming: Kimo Talks’ (June 2015) and ‘Keep-Kenya Education Empowerment Project’

(March 2017). I have always encouraged my team members to utilise appreciative action skills to complement each other in our different worlds of thought, realising our common goals while appreciating our differences.

Kimo Wellness Foundation and AI

The Kimo Wellness Foundation is the brain-child of a group of community volunteers with different professional backgrounds, ranging from counsellors and psychologists through social workers, addiction practitioners, teachers

and public health workers to medical practitioners. The members either were born in Kenya or have an interest in working with the diverse communities in the country. They embrace the twenty-four internationally accepted character strengths highlighted in the VIA Survey.

The team has learned how to appreciate each other, expressing a willingness to work together without trying to reconcile their differences in terms of ethnicity, education, colour or even economic status. And as the Kimo team puts it: “We appreciate our differences; we look at the differences as strengths. When unleavened outwardly, the strengths help us to relieve human suffering among the communities within the Kenyan community. We appreciate our rich diversity of culture, always trying to make ‘better bread’ out of our rich ethnicity of fortythree different communities.” It is important to note that our country, Kenya, has had a history of ethnic divide in terms of available resources, including employment. Our target population is a mix of the various ethnic groups that co-exist in Kenya. The institutions are an all-round representation of the diversity of citizens, ethnically and politically.

Through appreciating each other, the dialogic process has offered solutions to creatively care for relationships and in reducing the destructive potential of conflict, hence realising a peaceful co-existence among children, the future of our nation. When teachers experience what they teach to children, they learn to appreciate the learners.

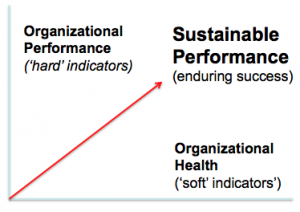

The Kimo team is working with schools to tap the potential toward improved academic performance in the schools. The team has come up with innovative phases to identify and assess character strengths and develop a language of

strengths, using the AI process as well as a set of character strengths and core virtues recognised across world cultures.

To start with, teachers are engaged in identifying and appreciating their own strengths, which helps avoid conflict among the teaching staff. When they learn about their different strengths, each member experiences and appreciates being complementary to the other, rather than a threat. This comes with cultivating good relationships, a healthy community and good citizenship among the diverse ethnic group of teachers. They look at each other

as “rose flowers” from one family, though with different colours. And as we say in the Kimo team: “They can walk the journey together even without trying to reconcile their differences.” This is even more so when parents become part of the learning team; they become more committed to provide for their children’s basic needs in school.

Fostering self-driven behaviour and ownership

Children enjoy being part of the larger community as they struggle to raise their voices higher for improved academic performance. Children learn to appreciate reflecting on and spreading their character strengths outwardly. This fosters self-driven behaviour and ownership in a learning community. Character strengths such as kindness, love for learning, teamwork, humour, selfregulation and social intelligence are enhanced.

I am optimistic that working with diverse communities will one day give birth to an appreciative group of citizens in Kenya, and the tread will impact positively on other African countries, and eventually out into the wider world. I believe in continuing my work as a symbol of appreciative practice in the world.

Footnotes:

(1) Fialkov, C., Haddad, D., Ndirangu, N., & Kamau, J. (2015). Tukae Tusemsane:

Let’s Sit Down and Reason Together: Enlivening Strengths and Community.

World Appreciative Inquiry Conference (WAIC), Johannesburg South Africa 2015

http://www.2015waic.com/images/Abstracts/ai15abstract00019.pdf

(2) Fialkov, C., Ndirangu, N., Karanja, J., & Haddad, D. (2015). Tukae Tusemesane:

Let’s Sit Down and Reason Together. AI Practitioner, International Journal of Appreciative Inquiry.

https://aipractitioner.com/product/

tukae-tusemesane-let-s-sit-down-and-reason-together/

(3) Further information on the Kimo Wellness Foundation can be found at the following link: www.

kimowellnessfoundation.org

About Nelly Nduta Ndirangu

Nelly Nduta Ndirangu is a co-founder of the Kimo Wellness Foundation, an International non-profit organisation based in Kenya. A seasoned, practising counselling psychologist and supervisor, having trained in addiction

counselling and testing, child counselling, teaching and trauma healing, Nelly is also the proprietor of the Kimo Wellness Counselling Centre. She holds a BA in Counselling Psychology and is earning her Masters in Counselling Psychology at the Kenya Methodist University.